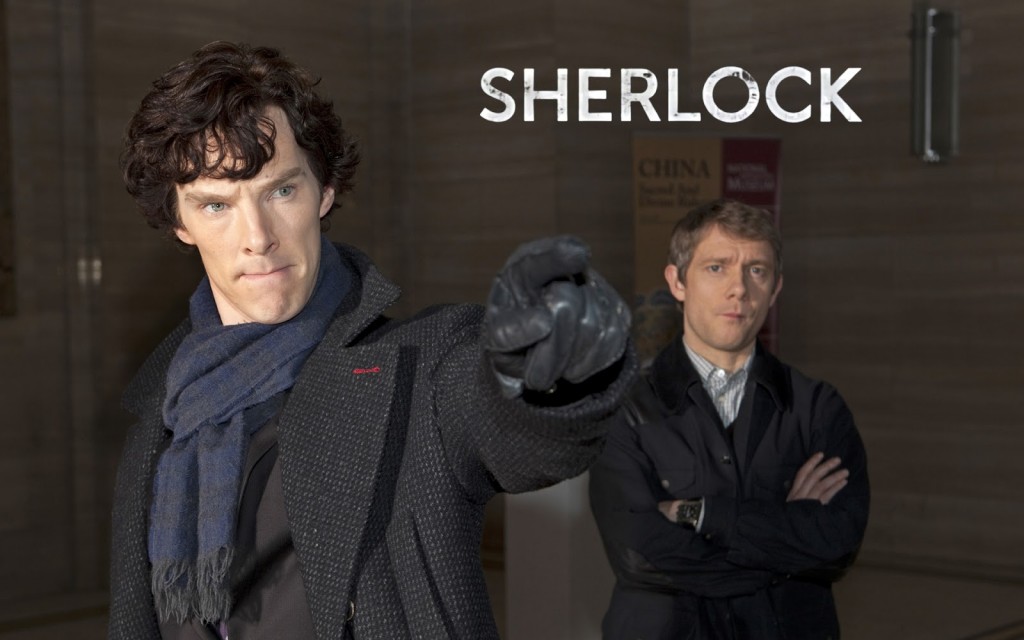

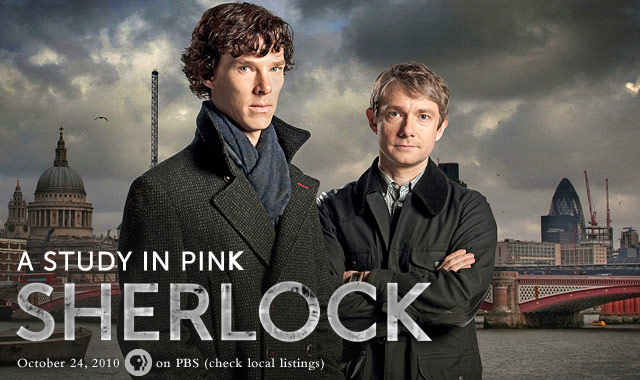

Sunday January 19th is the night all Americans will be treated to the return of Sherlock, the BBC’s top-notch series based on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle‘s Sherlock Holmes. There have been many, many adaptations of Doyle’s stories and novels to the big and small screens over the last 100+ years, but fans will have their favourites and this incarnation ranks near the top for me. I grew up a voracious reader and loved being read to more than anything. My father traveled for work more and more the older I got and since he couldn’t read to me himself he got in the habit of finding me books on tape. The best were definitely Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce reading The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. I soon had all the stories memorized, but still the drama of hearing the tales read aloud mesmerized me. And no matter how many times I heard it, The Speckled Band scared me so much I could barely fall asleep. When I got a little older I read most of the stories in books and only after that did I become interested in seeing my hero portrayed. As someone who loved the original stories first, it can be hard to watch some of the films and shows that have come out purporting to be about Sherlock Holmes, the latest of which include the films starring Robert Downey, Jr. and the American series Elementary. The former might have been good fun had Conan Doyle never picked up a pen and the latter, well…the kindest thing I can say is that I really wanted to like it, but that simply wasn’t possible. The films starring Rathbone and Bruce were somehow less compelling to me than their readings had been. No, my Sherlock Holmes was Jeremy Brett and still is as far as strict adaptation goes. (The genius of that performance requires its own post someday.) But the brilliance of Sherlock lies in its modernization of the characters and their preoccupations while keeping true to the spirit of the original works. And it does this so brilliantly that I’ve been counting down to the release of the upcoming third series for well over a year. Now that we’re in the home stretch I thought I’d take a little time over the next six days to revisit the previous six episodes. If you’d like to do the same they are available through Netflix and Amazon Instant Video.  A Study in Pink is a close adaptation of Conan Doyle’s first story, A Study in Scarlet, and with both the real draw isn’t the central crime but the introduction of the characters. Sherlock is everything you remember him to be—entitled, well dressed, out of step with humanity, keen, and dazzling—but now he texts. Technology has afforded him the opportunity to keep people a bit farther than at arm’s length. Did you for a moment think he wouldn’t take it? Watson, on the other hand, is all he was meant to be and plenty of it as you’ve never seen him portrayed before. He is a doctor, but much more noticeably a soldier fresh from the war in Afghanistan (worth noting, the same place Conan Doyle’s Watson had just returned from serving). He’s depressed and a little desperate for not being amid conflict and facing life or death consequences to his actions. Audiences generally accept this pair as a literary tradition, but the creators of this series took the time to think about what would make John Watson want to put up with Sherlock Holmes and vice versa and the work they do establishing the basis of the relationship pays off throughout the series.

A Study in Pink is a close adaptation of Conan Doyle’s first story, A Study in Scarlet, and with both the real draw isn’t the central crime but the introduction of the characters. Sherlock is everything you remember him to be—entitled, well dressed, out of step with humanity, keen, and dazzling—but now he texts. Technology has afforded him the opportunity to keep people a bit farther than at arm’s length. Did you for a moment think he wouldn’t take it? Watson, on the other hand, is all he was meant to be and plenty of it as you’ve never seen him portrayed before. He is a doctor, but much more noticeably a soldier fresh from the war in Afghanistan (worth noting, the same place Conan Doyle’s Watson had just returned from serving). He’s depressed and a little desperate for not being amid conflict and facing life or death consequences to his actions. Audiences generally accept this pair as a literary tradition, but the creators of this series took the time to think about what would make John Watson want to put up with Sherlock Holmes and vice versa and the work they do establishing the basis of the relationship pays off throughout the series.

The two are brought together by a mutual acquaintance who hears them both remark on looking for a flat-mate in London. As with most people Watson is at first put off by Sherlock’s behavior, but not more than he is intrigued by it. Watson googles him, but we don’t get to see what pops up. We only know that the next day he shows up to see the flat at 221B Baker Street, Detective Inspector Lestrade appears to consult Sherlock on an investigation, and it isn’t until they are on the way to the crime scene that we are granted the recitation of observations we’ve been waiting for—how Sherlock knew, just by looking at him, nearly all of what Watson was about.

The two are brought together by a mutual acquaintance who hears them both remark on looking for a flat-mate in London. As with most people Watson is at first put off by Sherlock’s behavior, but not more than he is intrigued by it. Watson googles him, but we don’t get to see what pops up. We only know that the next day he shows up to see the flat at 221B Baker Street, Detective Inspector Lestrade appears to consult Sherlock on an investigation, and it isn’t until they are on the way to the crime scene that we are granted the recitation of observations we’ve been waiting for—how Sherlock knew, just by looking at him, nearly all of what Watson was about.

“I didn’t know, I saw. Your haircut, the way you hold yourself, says military. The conversation as you entered the room said trained at Bart’s, so Army doctor. Obvious. Your face is tanned, but no tan above the wrists—you’ve been abroad, but not sunbathing. The limp’s really bad when you walk, but you don’t ask for a chair when you stand, like you’ve forgotten about it—so it’s at least partly psychosomatic. That suggests the original circumstances of the injury were probably traumatic—wounded in action then. Wounded in action, suntan—Afghanistan or Iraq.”

“You said I had a therapist,” Watson interjects.

“You said I had a therapist,” Watson interjects.

“With a psychosomatic limp? Of course you have a therapist.”

The act goes on as an echo of the original with the object of Sherlock’s further observation updated from Watson’s watch to his phone, the one accessory that everyone carries in this day and age.

“That…was amazing,” Watson says.

“You think so?”

“Of course it was. It was extraordinary. It was quite extraordinary.”

“That’s not what people normally say,” Sherlock responds.

“What do people normally say?” Watson asks.

“Piss off.”

Watson is ditched at the crime scene by a seemingly thoughtless Sherlock, clearly consumed by other thoughts at that moment, only to be whisked off cloak and dagger style to an abandoned warehouse for a troubling conversation with a very mysterious man.

“I’m the closest thing to a friend that Sherlock Holmes is capable of having,” says the man.

“I’m the closest thing to a friend that Sherlock Holmes is capable of having,” says the man.

“And what’s that?” Watson asks.

“An enemy.”

The man interrogates him as to his connection with Sherlock and then offers Watson money to spy for him. Watson refuses, but as the conversation proceeds you notice this man is perhaps quite dangerous. He knows things he shouldn’t and he sees things as clearly as Sherlock does. He tells Watson he knows people have warned him to stay away from Sherlock and he also knows he’s not going to do it. He knows Watson has an intermittent tremor in his left hand that his therapist has diagnosed as PTSD and he knows her diagnosis is wrong because even now, in the midst of danger, his hand is completely steady. “You’re not haunted by the war, Dr. Watson,” the man says. “You miss it.” Who is he? I suspect Moriarty, but we must wait and see.

And then there is poor Lestrade, who is less introduced than ever-present and trod upon. He is mocked by Sherlock’s texts to the gathered journalists during his press conference and then has to ask Sherlock to consult on his case and in so doing admit he and his team are totally stumped. Having shown his desperation he is hard pressed to get out of Sherlock what he brought him in to find—namely evidence—resulting in the hilarious bit of business that is his ‘drugs bust’ on Sherlock’s apartment midway through the episode. Of course Lestrade’s entire squad volunteers for the exercise, all of them sick of being made fools of by Sherlock. “They’re not strictly speaking on the drugs squad,” Lestrade says, “but they’re very keen.”

In front of Watson and Mrs. Hudson and the squad the two men go back and forth over Lestrade’s alleged trespass and the evidence Sherlock has allegedly concealed until Anderson,  the much disdained forensics expert, begins intimating that Sherlock is really the killer. “I’m not a psychopath, Anderson,” Sherlock insists, “I’m a high functioning sociopath. Do your research.” As he argues with all of them the details of the crime coalesce for him, though of course not for them. Consumed again by more immediate concerns he ducks out the door and into the killer’s taxi out front. As they scramble to catch up with him, figuratively and literally, Watson asks Lestrade why he puts up with Sherlock. “Because I’m desperate,” admits Lestrade. “And because Sherlock Holmes is a great man. And I think one day if we’re very, very lucky he might even be a good one.”

the much disdained forensics expert, begins intimating that Sherlock is really the killer. “I’m not a psychopath, Anderson,” Sherlock insists, “I’m a high functioning sociopath. Do your research.” As he argues with all of them the details of the crime coalesce for him, though of course not for them. Consumed again by more immediate concerns he ducks out the door and into the killer’s taxi out front. As they scramble to catch up with him, figuratively and literally, Watson asks Lestrade why he puts up with Sherlock. “Because I’m desperate,” admits Lestrade. “And because Sherlock Holmes is a great man. And I think one day if we’re very, very lucky he might even be a good one.”

As Sherlock follows the psychopath serial killer into an abandoned building we are reminded of Lestrade’s warning to the public at the beginning of the episode, “All anyone has to do is exercise reasonable precautions. We are all as safe as we want to be.” If we’ve learned anything since then it’s that Sherlock is not a reasonable man, not in practical terms, and  Watson understands this better than the rest. He tracks the killer’s cab and watches the two of them interacting from a building across the way. He can’t hear them talking, but observing them the details finally coalesce for him as well—he understand that Sherlock is in grave danger and he shoots the killer dead.

Watson understands this better than the rest. He tracks the killer’s cab and watches the two of them interacting from a building across the way. He can’t hear them talking, but observing them the details finally coalesce for him as well—he understand that Sherlock is in grave danger and he shoots the killer dead.

We next see Sherlock in the back of an ambulance, a blanket ridiculously forced on him to comfort his shock. Lestrade is remarking on how lucky they are the way things turned out, but Sherlock insists a dangerous man is still on the loose. “The bullet they just dug out of the wall is from a handgun. A kill shot like that over that distance from that sort of weapon, you’re looking for a crack shot, but not just a marksman. His hands musn’t have shaken at all so clearly he’s acclimatized to violence. He didn’t fire until I was in immediate danger, so obviously has a strong moral principle. You’re looking for someone probably with a history of military service and nerves of steel—” he breaks off as soon as he spots Watson waiting on the other side of the crime scene tape. “Ignore all of that,” he says, “it’s just the shock talking.”

This ending is a departure from the original story, but again it functions in the spirit of the original. Conan Doyle’s Watson was not a joke. While Holmes regularly insulted his intelligence in the stories, it was merely the recognition of otherness—not that Watson was definitively an inferior being but rather that he, like the rest of us, was not Holmes. Watson’s performance in this ending rather blatantly presents us with several of the reasons that Sherlock values his companionship. At the same time it reveals that Watson does see past Sherlock’s genius and is learning to recognize his shortcomings and anticipate his pitfalls.

As they congratulate each other on the conclusion of the caper, Watson says, “That’s how you get your kicks, isn’t it? You risk your life to prove you’re clever.” Sherlock comes back with a halfhearted denial, but before they can get into it Watson spots the mysterious man from the warehouse. “Sherlock, that’s him,” he says, “that’s the man I was talking to you about.” They walk over to the man and Sherlock recognizes him immediately. They banter back and forth with rhetorical barbs until the man says, “This petty feud between us is simply childish. People will suffer. And you know how it always upset mummy.” Watson’s jaw drops and so did mine. And then I smiled as Sherlock said, “I upset her? Me? It wasn’t me who upset her Mycroft.” And there you have it, another key character deftly introduced.